A year in the art world

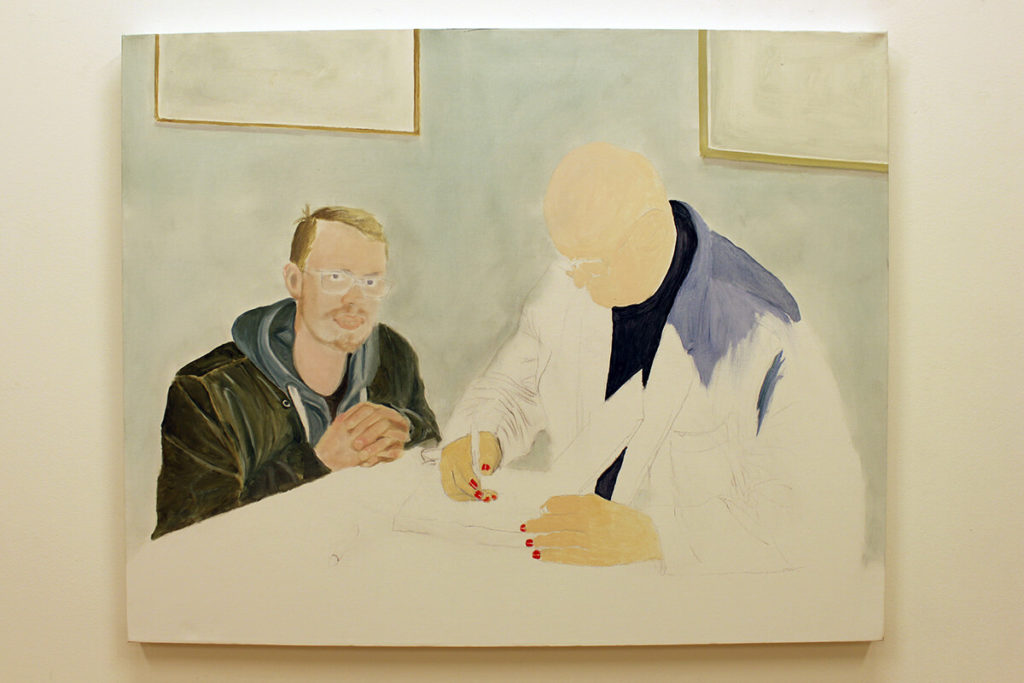

The artists Rán Jónsdóttir and Unnur Óttarsdóttir exhibit paintings and photographs at the exhibition A year in the art world. The paintings and photographs exhibited are based on their travels through the Icelandic art scene, where they were mirrored by each other as well as other contemporary artists. The artists made the works collaboratively.

Four paintings is not a large number of works for an art exhibition. Indeed, the artists are still deciding whether there will only be three. It is not so much that the works are not yet finished, as that they are still emerging, not just physically but conceptually. And the works themselves have this emergent quality too. In the previous century one might have talked about “becoming” – about a kind of ambivalent emergence in which the identity of something is constructed at the same time as it is physically made. What is the identity of these works, and what do they tell us about the artists’ relationship to their surroundings?

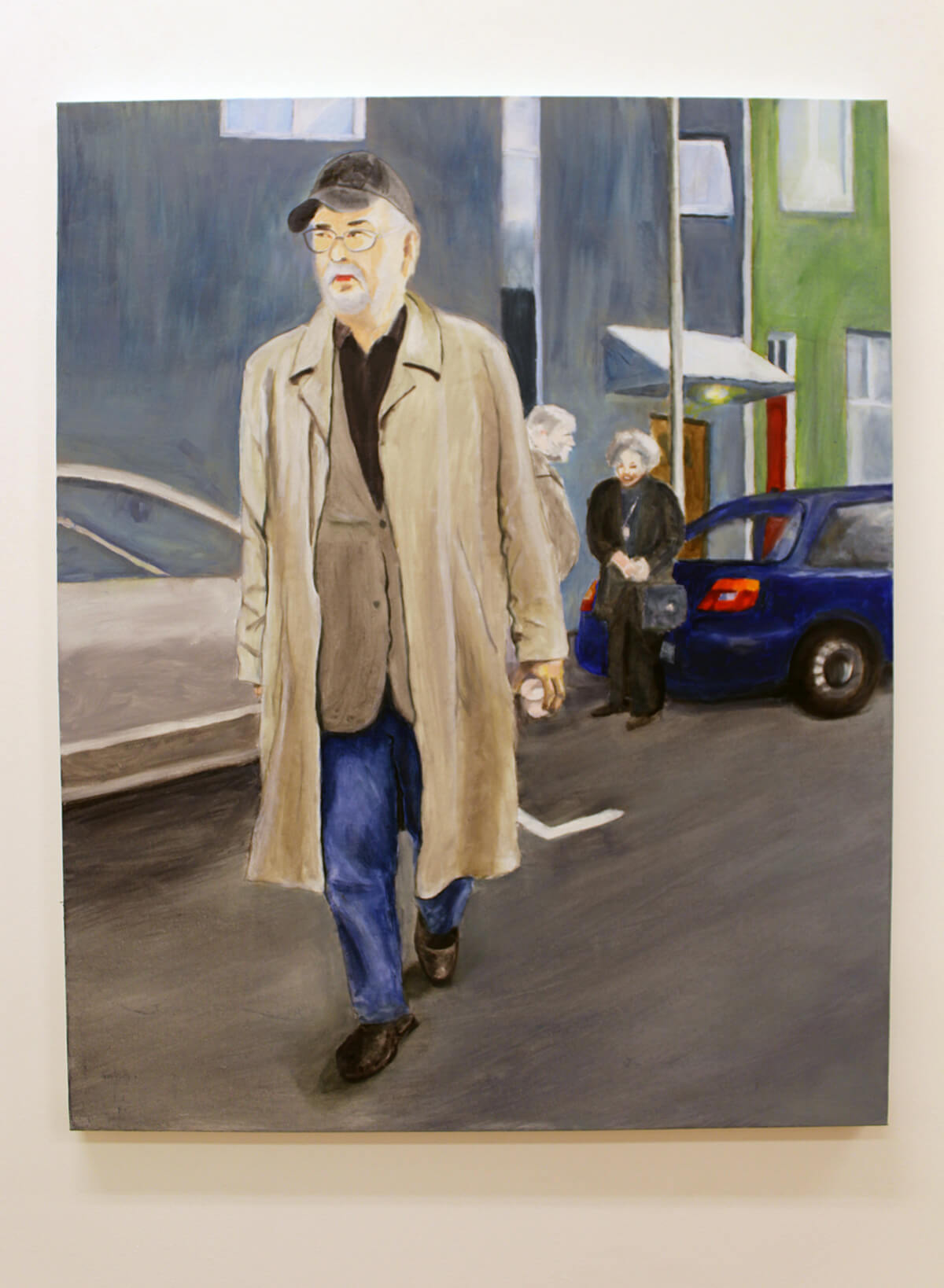

Each of these paintings depicts an icon from the world of Icelandic art. Treated chronologically, the starting point is Stefánsson’s “Sumarnótt, Lómar við Þjórsá” from 1929 – painted before Iceland was an independent nation, an eerie landscape populated by two Protean birds. Empty. A blank canvas with only some Nature written on it. Then we have three works featuring the Icelanders. They have not exactly arrived, but seem to be in the process of arriving, of settling down, of finding their topic. Two icons of Icelandic art production, Magnus Pálsson, and Kristján Guđmundsson, both of whom have represented Iceland at the Venice Biennale, embody the process the whole world was going through in the second half of the 20th century: a desperate struggle to find a new identity in which the old nationalistic boundaries had been redrawn. A process all the more pressing for the Icelanders who had to over-paint their identity on the empty canvas supplied by Stefánsson. And so the heroes of Icelandic conceptual art are in some way embodying the sense in which contemporary artists such as Unnur Óttarsdóttir and Rán Jónsdóttir have to find their identity – in a world of representation and misrepresentation, of media images, photography, and art in which concepts perhaps feature more strongly than images.

From Kristján’s postcards, “Tourist poem” from 2015 about a strange and apparently unvisited land to Stefánsson’s landscape devoid of people – the present exhibition invites us to think what it is to be an Icelander. It is an identity that is laid over a place that has a strong identity, albeit empty and blank as those unwritten postcards or a Summer Night. These four, or is it three, paintings reveal how many layers of reference and identity-building there are in any artistic production in the 21st-century, but perhaps more than most in the production from that emergent place that is contemporary Iceland.

Michael Biggs professor of aesthetics